Aimee Dunkle often ruminates about the call that could have saved her son’s life.

A friend was with her 20-year-old son when he was in the grips of a heroin overdose in 2012, but the young man never called 911 for fear he’d be locked up for violating the terms of his drug diversion program. Ben suffered a catastrophic brain injury as a result of the delay in getting medical help. He died after eight days on life-support.

More than a decade later, as fatal opioid overdoses are skyrocketing across the U.S., Dunkle, 63, and other grieving family members have joined forces to call for compassionate treatment rather than criminalization of drug users like Ben’s friend.

These types of punitive drug laws, Dunkle said, “cost my boy his life.”

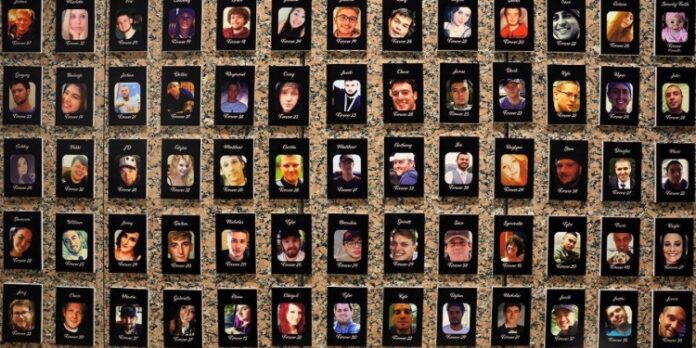

As more than 100,000 people died from overdose deaths for a second consecutive year, lawmakers proposed a slew of bills aimed at doling out harsher sentences – including murder charges – for people who sell or distribute drugs such as fentanyl, a synthetic opiate that’s exponentially stronger than heroin. Families who have lost children to overdoses say such policies won’t reduce deaths like those their relatives suffered. Instead, they’ll push chronic health issues of addiction into prisons. They will perpetuate but not curtail the country’s decades-long war on drugs, the families said.

“We all want to see a reduction in overdose deaths, but punishment is not the answer,” Dr. Tamara Olt, a mother from Peoria, Illinois who lost her 16-year-old son Josh to an opioid overdose in 2012, said at a recent news briefing.

Olt serves as executive director of Broken No More, an organization founded by families and friends of people with substance use disorders. The organization held a virtual news conference in the lead-up to Mother’s Day to share their support for drug policies informed by evidence-based public health practices, rather than punitive approaches.

In September, hundreds of grieving family members issued an open letter to lawmakers to call for “lifesaving health responses to the overdose crisis.” They pushed back on laws that establish murder charges for “drug-induced homicide” if someone sells or shares drugs that result in a fatal overdose and on mandatory minimum sentences and increased punishment for drug use. Instead, the letter urged lawmakers to find ways to decriminalize drugs and work on providing better access to needle exchanges and overdose-reversing medications like naloxone, and focus on evidence-based treatment options and broadening education on opioid use disorder.

States shift approach on fentanyl

Several states have changed the penalties for distributing or manufacturing fentanyl, according to an August analysis by the National Conference of State Legislatures. This includes new laws in Arkansas and Kansas that impose life imprisonment for manufacturing fentanyl that could appeal to a minor through shape or packaging. Tennessee also allows prosecutors to charge people with murder if they give fentanyl to a person who dies from an overdose.

While these laws have cropped up in Republican-led states that traditionally embraced tougher drug laws, advocates at the briefing this week warned that Democratic-leaning states are embracing similar approaches at the peril of people suffering from substance use disorder.

In 2021, Oregon became the first state to decriminalize illicit drugs. The policy, backed by the American Pharmacists Association, would allow people using illegal substances to retain their employment while involved in treatment. But following the recent explosion in synthetic opioid deaths, the blue state brought back criminal punishment for use and possession of narcotics in 2024. The law never had a chance to work, Jeffrey Bratberg, clinical professor in the University of Rhode Island College of Pharmacy, told USA TODAY at the time the law was reversed.

California, where Dunkle lives, has also shifted its drug policies, cracking down harder in recent years on people who perpetuate use. In her son Ben’s memory, in 2015, Dunkle founded the nonprofit Solace Foundation of Orange County, the first naloxone distribution program in her region of Southern California. Dunkle also began distributing fentanyl test strips and worked with a needle exchange until Santa Ana city officials shut it down in 2018.

After that, Dunkle said, “I took to the streets of Santa Ana with a backpack to hand out supplies and naloxone.”

In the years she’s been focused on these issues, she’s seen a push for punitive measures fueled by other grieving families. She has thought long and hard about that. But she’s seen that, all too often, the people who give someone a drug that causes a fatal overdose are also users. Fentanyl − a drug far more powerful than heroin that replaced it on streets in the U.S. in recent years − poses even greater danger to people with substance use disorders.

“They didn’t choose fentanyl,” she told USA TODAY. “Fentanyl was chosen for them.”

One instance of families pushing for harsher laws is a bill by California State Senator Tom Umberg, D-Orange County, whose legislation “Alexandra’s Law” requires educating people convicted of distributing opioids publicly within the court setting. The bill requires a judge to read a “fentanyl admonishment” to anyone convicted of a fentanyl-related drug offense, stating, “You are hereby advised that all illicit drugs and counterfeit pills are dangerous to human life and become even deadlier when they are, sometimes unknowingly, mixed with substances such as fentanyl and analogs of fentanyl.” The bill is named after a 20-year-old Temecula, California woman, Alexandra Capelouto, who died from a fentanyl overdose. Several families who lost loved ones to fentanyl overdoses, including Capelouto’s family, backed the bill.

The admonishment is similar to statements judges must read to people convicted of a DUI. The current draft language for “Alexandra’s Law” says that if a convicted person sells or administers fentanyl in the future that results in someone’s death, they could be charged with murder. The bill is stuck in the state Legislature.

“While any purchase of drugs from the street or black market inherently carries a risk, what we are seeing today is the unprecedented poisoning of young Americans,” Umberg, a former prosecutor, said in a statement to USA TODAY. “There is no fear of addiction, or need to ask for help when a victim dies almost immediately of a substance they never assumed would kill them.”

Dunkle said such legislation doesn’t address the overdose problem in its entirety, especially for young people like the man who was with her son when he overdosed. Umberg, a lawmaker in Dunkle’s county, said in his statement that he knew Dunkle and felt for her family and others who have lost loved ones to the opioid crisis.

However, he refuted the notion that California is prosecuting fentanyl users by applying harsher penalties, and putting them behind bars instead of offering treatment.

“To suggest so and equate it to the ‘War on Drugs’ is dangerously misleading and borderline irresponsible,” Umberg said. “This epidemic requires an ‘all in/every tool’ approach to the crisis,” including prevention, education, treatment and stopping repeat sellers. “Arresting and prosecuting fentanyl dealers alone is an insufficient response to meet this crisis,” he said.

Dunkle said she understands the anger that families feel. She felt it, too, after Ben’s death. But it changed a few weeks after his death. Her younger son, then 17, bumped into Ben’s friend who had refused to call for help the day of the overdose. The friend looked terrible, her younger son said.

She wanted people to look for light out of the darkness, she said. Fentanyl overdoses happen quickly. People should feel assured that saving their friends is not just the right thing, it’s something they can safely do without being punished.