A 2018 report from the Environmental Protection Agency found that people of color are much more likely to live near polluters and breathe polluted air. “Poison is the wind that blows from the north and south and east.” Marvin Gaye wasn’t an environmental scientist, but his 1971 single “Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)” provides a stark and useful environmental analysis, complete with warnings of overcrowding and climate change. The song doesn’t explicitly mention race, but its place in Gaye’s What’s Going On album portrays a Black Vietnam veteran, coming back to his segregated community and envisioning the hell that people endure.

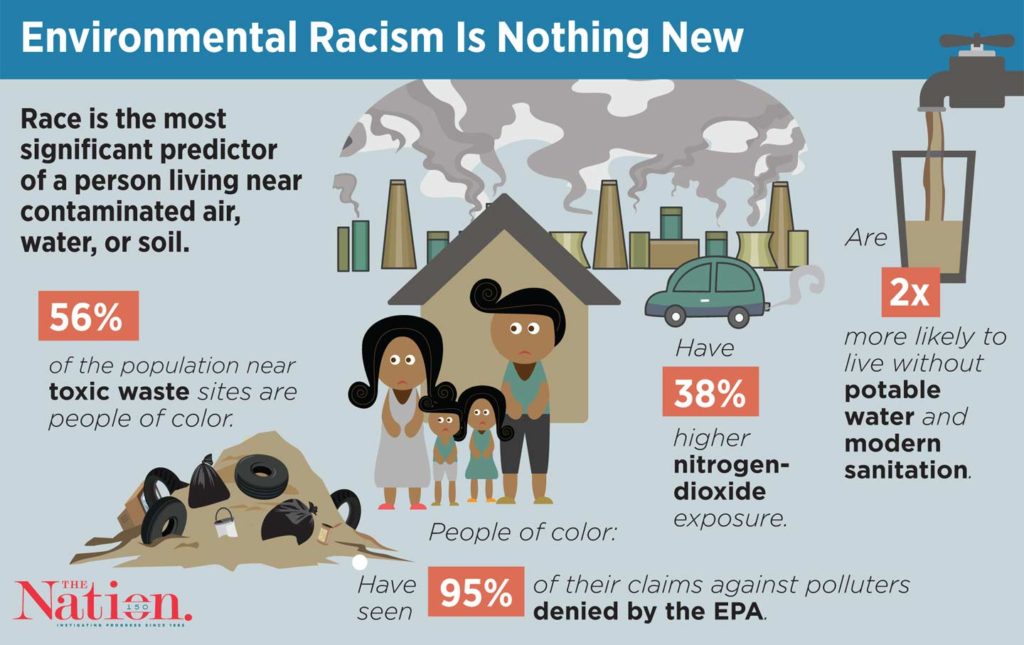

Gaye’s prophecies relied on the qualitative data of storytelling—of long-circulated anecdotes and warnings within Black communities of bad air and water, poison, and cancer. But those warnings have been buttressed by study after study indicating that people of color face disproportionate risks from pollution, and that polluting industries are often located in the middle of our communities.

According to the study’s authors, “results at national, state, and county scales all indicate that non-Whites tend to be burdened disproportionately to Whites.” The study focuses on particulate matter, a group of both natural and manmade microscopic suspensions of solids and liquids in the air that serve as air pollutants. Anthropogenic particulates include automobile fumes, smog, soot, oil smoke, ash, and construction dust, all of which have been linked to serious health problems. Particulate matter was named a known definite carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer, and it’s been named by the EPA as a contributor to several lung conditions, heart attacks, and possible premature deaths. The pollutant has been implicated in both asthma prevalence and severity, low birth weights, and high blood pressure. As the study details, previous works have also linked disproportionate exposure to particulate matter and America’s racial geography. A 2016 study in Environment International found that long-term exposure to the pollutant is associated with racial segregation, with more highly segregated areas suffering higher levels of exposure. A 2012 article in Environmental Health Perspectives found that overall levels of particulate matter exposure for people of color were higher than those for white people. That article also provided a breakdown of just what kinds of particulate matter counts in the exposures. It found that while differences in overall particulate matter by race were significant differences for some key particles were immense. For example, Hispanics faced rates of chlorine exposure that are more than double those of whites. Chronic chlorine inhalation is known for degrading cardiac function.

It seems that almost anywhere researchers look, there is more evidence of deep racial disparities in exposure to environmental hazards. In fact, the idea of environmental justice—or the degree to which people are treated equally and meaningfully involved in the creation of the human environment—was crystallized in the 1980s with the aid of a landmark study illustrating wide disparities in the siting of facilities for the disposal of hazardous waste.

The idea of environmental racism is, like all mentions of racism in America, controversial. Even in the age of climate change, many people still view the environment mostly as a set of forces of nature, one that cannot favor or disfavor one group or another. The EPA’s own research shows what Marvin Gaye saw 50 years ago: the burden will be increased most on people of color.