The charge, while provocative, offers a framework to reckon with systemic racial injustice — past and present.

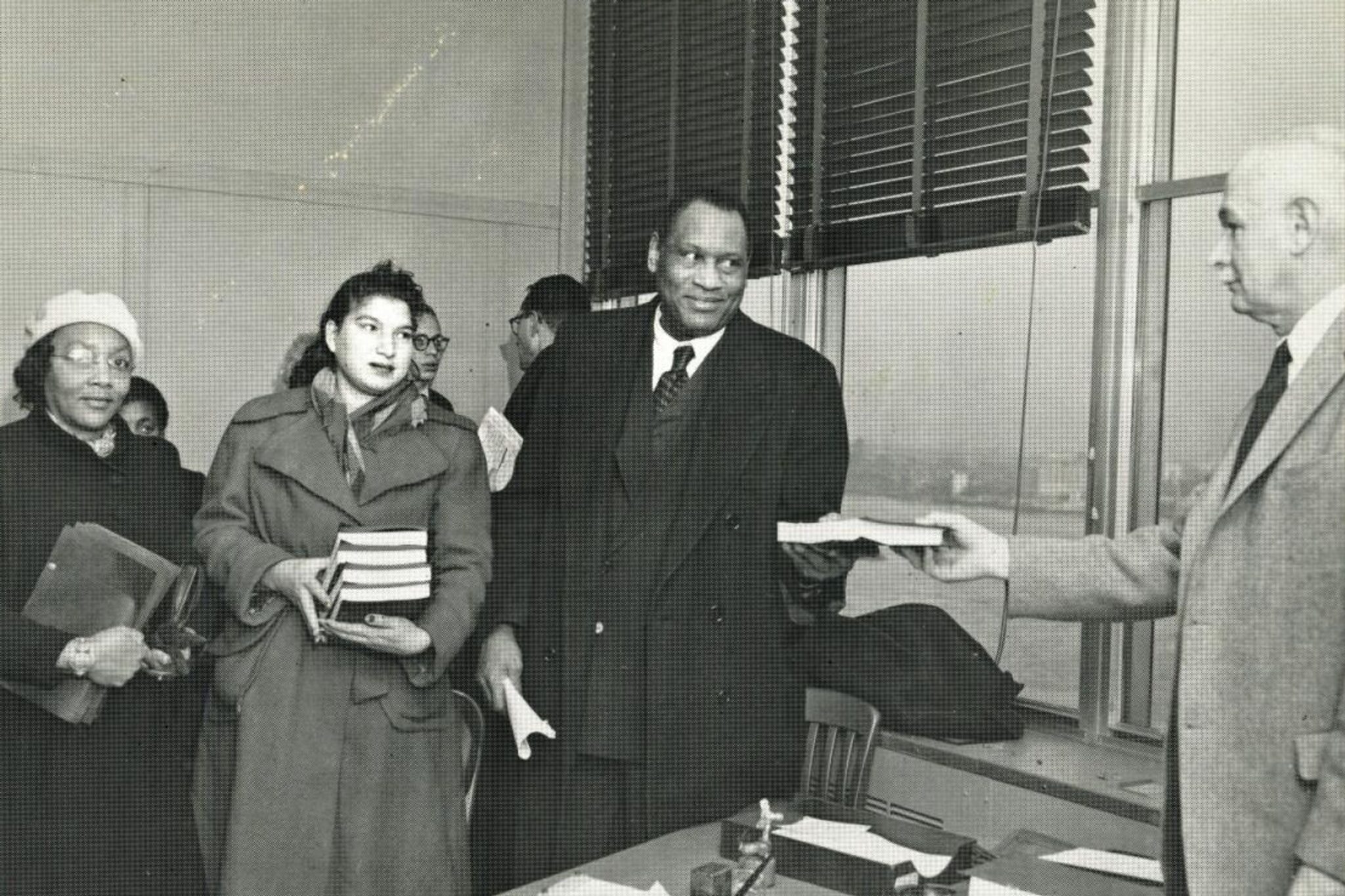

Seventy years ago this month, on Dec. 17, 1951, the United Nations received a bold petition, delivered in two cities at once: Activist William Patterson presented the document to the U.N. assembly in Paris, while his comrade Paul Robeson, the famous actor and singer, did the same at the U.N. offices in New York. W.E.B. Du Bois, a leading Black intellectual, was among the petition’s signatories.

The group was accusing the United States of genocide — specifically, genocide against Black people.

The word “genocide” was only seven years old. It had been coined during World War II in a book about Nazi atrocities, and adopted by the United Nations in 1948, though no nation had yet been formally convicted of perpetrating a genocide.

The 240-page petition, “We Charge Genocide: The Crime of Government Against the Negro People,” was meant to be sensational. America had been instrumental in prosecuting the Nazis at Nuremberg, and now its own citizens were turning the lens back on the U.S. in the most horrifying, accusatory terms.

Instead, mainstream media largely ignored it. The New York Times and Washington Post mentioned the petition in brief stories buried in the back pages. The Chicago Tribune condemned it for “shameful lies.” Raphael Lemkin, the Polish jurist who had coined the term “genocide,” publicly disagreed with the whole basis of the petition, saying it confused genocide with discrimination.

But today, 70 years later, the document has a new resonance amid the patent injustices of police brutality that continue to occur and racial inequities in health care on display especially throughout the pandemic. “We Charge Genocide” explored these kinds of issues at length, making a compelling case for thinking about structural racism as genocide, which demands not only condemnation but also redress and repair. To consider the arguments in “We Charge Genocide,” drafted by some of the most notable figures in the midcentury civil rights movement, offers important insights into the current moment and how to move forward.

“Genocide” seems — and is — hugely divisive, and it’s unlikely that the U.N. would formally accuse its wealthiest member of the crime, even in the past. But the petitioners weren’t wrong to situate Black American history in that bleak context, and doing so gives us — maybe surprisingly — some routes forward.

The U.N. remediation guidelines for mass human rights violations like genocide have some clear goals. These include safeguarding basic human rights of the offended group, investigating abuses and providing redress.

What might such remedy look like? Monetary payment is an obvious form of compensation, and an establishment of genocide can help advance current discussions around such reparations. Efforts to remedy historical injustices in other parts of the world offer other examples — education, health services, criminal trials, structural reforms — that have also been implemented in response to genocide. And even in the face of only accusations, let alone convictions, of genocide, truth-seeking commissions have been held to take seriously the charge and determine and acknowledge the extent of abuse.

As the U.S. reckons with how to address its racial injustices, past and present, such examples of remedy for mass human rights violations give us a framework to think about how to do it justly and with full acknowledgment of the wrongs committed.