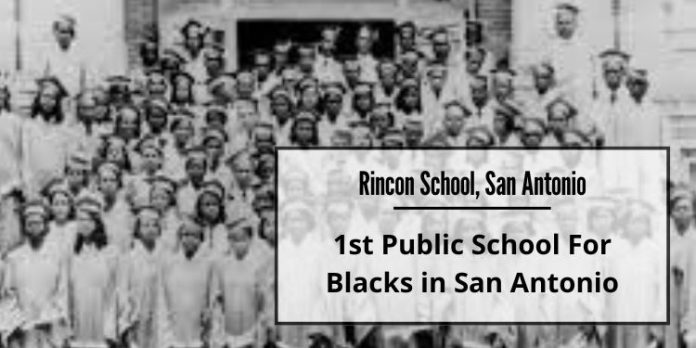

Jim Crow Black School History in San Antonio

The first public school for Black children and adults in San Antonio was the Rincon School, named after Rincon Street (now St. Mary’s) where it was originally located. It was founded in 1868 after the sale of a Confederate tannery and sawmill by the Bureau. Educating Black children during the day and adults at night, it quickly outgrew the two-story building. In 1888 additional rooms were rented in the St. James AME church to accommodate its many students. In 1889, George R. Brackenridge provided money to expand the Rincon School and extend it curriculum to include high school instruction, but this was limited to vocational training. This limited curriculum was based on the racist assumption that Black students possessed lower intelligence and a decreased wish to study academic subjects, as well as a desire to restrict Black employment to manual labor.

Additional segregated Black schools began to open to accommodate additional Black students: 1888 St. Peter Claver Catholic School, 1890 Santa Clara Public School on Center Street, and 1896 a Public African American School at the corner of Chavez and North Leonora. During this time the Rincon School also changed its name, becoming the Riverside School and then Frederick Douglas High School in 1915, when it moved to the Eastside near Mt. Zion First Baptist Church.

Opportunities for secondary education for Black students began in 1895, when Reverend James Steptoe Johnston, a white supremacist and Bishop of St. Philip’s Episcopal Church, began evening “Sewing Class for Negro girls.” This expanded into St. Philip’s Industrial Day

School on March 1, 1898, which was led by a white teacher, Mrs. Alice G. Cowan, who came from doing missionary work in Mexico, and its first full-time rector, a Black minister named Rev. William H. Marshall. The curriculum was racist and only offered classes in sewing, cleaning, repair work, gardening, cooking, and washing, as well as in serving and setting tables. No academic training for Black people at the time. Johnston believed training Black students for vocational jobs would prevent them from competing with whites in areas such as business and entrepreneurship that would imply Blacks were their equals.

In 1902, Artemisia Bowden was brought on as the teacher, principal, administrator, and chief fundraiser at St. Philip’s. Born in Georgia to formerly enslaved parents, she obtained her teaching credentials from St. Augustine’s School in Raleigh, North Carolina. When she arrived in 1902, she changed the name to “St. Philip’s Industrial School for Girls,” changing the curriculum to Departments for Primary (grades 1-5), Grammar (6-9), and Industrial (6-9) education while adding boarding facilities. Bowden made every effort to make sure students of any means could attend, accepting eggs, vegetables, or even livestock in exchange for the education. She raised money from Episcopal churches in the North and local San Antonio elite, such as Eleanor Brackenridge. In 1915 she moved St. Philip’s from its original location in La Villita to the outskirts of the Eastside, at 2120 Dakota Street, where it sits today.

Eventually, she grew the school to achieve private junior college status in May 1928, changing its name to St. Philip’s Junior College. While always struggling to find funds for the College, the 1930s and 40s were particularly challenging, and Bowden did not receive a full salary from 1935 to 1941, often paying teachers out of her own pocket. In 1942, St. Philip’s Junior College became affiliated with San Antonio Independent School District and San Antonio College (SAC). SAC was the white only college at the time and St. Philips was the Black college.